Stephanie SinclairToo Young To Wed documents children - some as young as 9 years old - forced into marriage in countries around the world. (Check out this New York Times article written by Sinclair and featuring some of her photos.) She also is the founder of the organization Too Young to Wed, whose mission is to empower girls and end child marriage globally. Like many photographers (real ones, and the rest of us who pretend), Sinclair posts photos on her Instagram account (@stephsinclairpix), which has nearly 170,000 followers. (I, deservedly, have 199.) If you try to follow Sinclair today (as I just did), you will learn that her account is now private. More on that in a minute.

(the plaintiff) is an award winning photojournalist whose haunting photo series

In 2016, Mashable (the defendant) published an article about Sinclair and nine other female photographers on mashable.com which included one of Sinclair's photos. (The article is still online, but Sinclair's photo is no longer there.) Initially, Mashable had reached out to Sinclair and offered $50 to use the photo. After she declined, Mashable instead used Instagram's publicly available API to embed in its article a photograph that Sinclair had posted on her (then public) Instagram account. As explained by the court (with citations omitted):

Embedding allows a website coder to incorporate content, such as an image, that is located on a third-party’s server, into the coder’s website. When an individual visits a website that includes an “embed code,” the user’s internet browser is directed to retrieve the embedded content from the third-party server and display it on the website. As a result of this process, the user sees the embedded content on the website, even though the content is actually hosted on a third-party’s server, rather than on the server that hosts the website.

You can find Instagram's explanation of how embedding works here.

When Mashable refused Sinclair's request to take her photo down, Sinclair sued Mashable (and its parent Ziff Davis) for copyright infringement. The defendants moved to dismiss the complaint. On Monday, Judge Kimba Wood granted the motion.

In their motion, the defendants argued that Mashable had a valid sublicense from Instagram to use the photo, and Judge Wood agreed. To reach this conclusion, the court had to wend its way through the various terms and policies that make up the "Permission Infrastructure" of Instagram. So here goes:

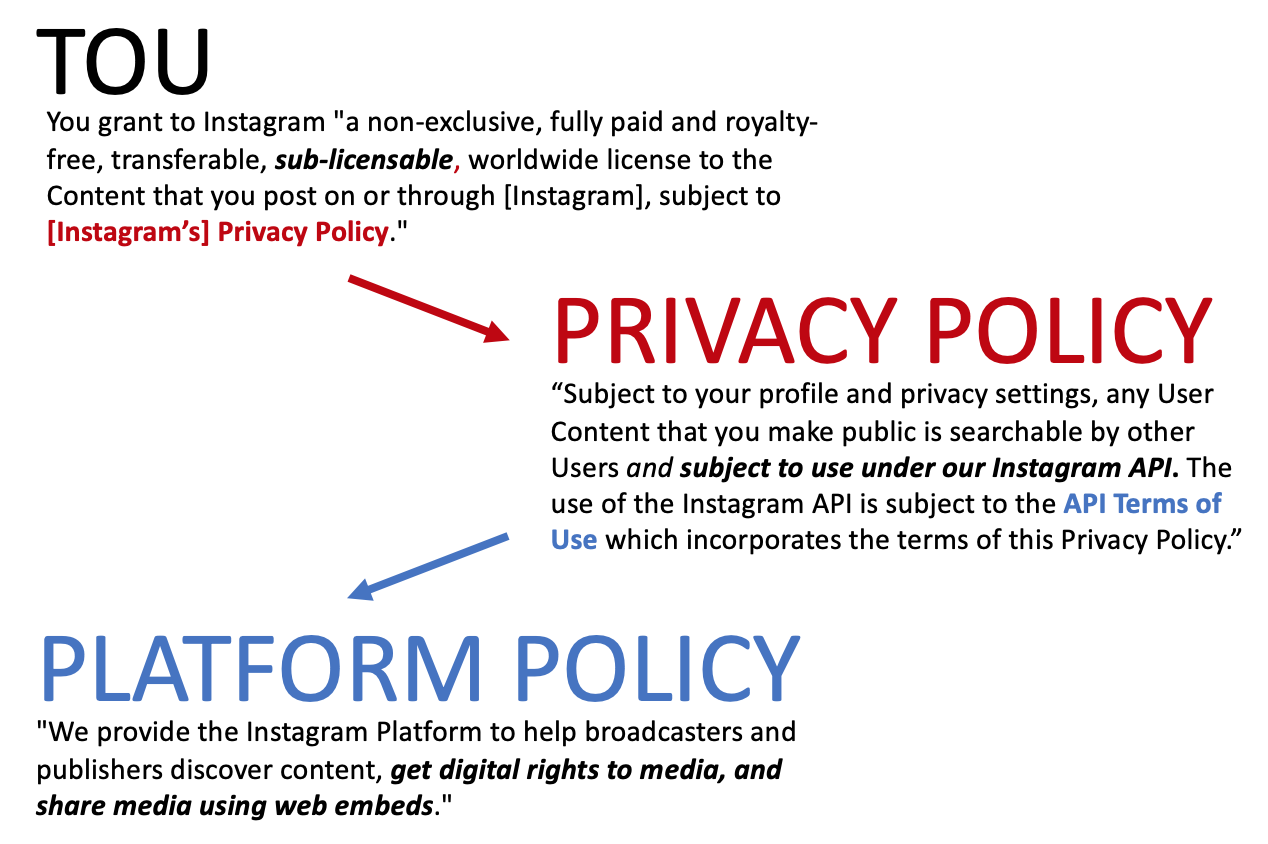

STEP 1: INSTAGRAM'S TOU: Terms of Use ("TOU"), a fact that she did not dispute. Pursuant to the TOU, all users of the platform (Sinclair included) grant to Instagram "a non-exclusive, fully paid and royalty-free, transferable, sub-licensable, worldwide license to the Content that you post on or through [Instagram], subject to [Instagram’s] Privacy Policy."

When she signed up to Instagram, Sinclair agreed to be bound by Instagram's

STEP 2: INSTAGRAM'S PRIVACY POLICY: Privacy Policy, in turn, provides that users can designate their accounts as “private” or “public” (and can change the setting at any time). Content posted on a public Instagram account is searchable by the world and subject to use by third parties (such as Mashable) via Instagram’s API. Specifically, the Privacy Policy provides:

Instagram's

Subject to your profile and privacy settings, any User Content that you make public is searchable by other Users and subject to use under our Instagram API. The use of the Instagram API is subject to the API Terms of Use which incorporates the terms of this Privacy Policy.

STEP 3: INSTAGRAM'S PLATFORM POLICY (API TERMS OF USE): (a.k.a as the Platform Policy), in turn, specifies that third parties that make use of Instagram's API - including publishers like Mashable - can embed on their websites content posted by Instagram user's on public accounts. For example, the preamble to the Platform Policy provides that Instagram "provide[s] the Instagram Platform to help broadcasters and publishers discover content, get digital rights to media, and share media using web embeds." The Platform Policy imposes other requirements on companies that use Instagram's API, including that they "[c]omply with any requirements or restrictions imposed on usage of Instagram user photos and videos" and they "[r]emove within 24 hours any User Content or other information that the owner asks you to remove."

The API Terms of Use

Thus, after stitching together the TOU, the Privacy Policy, and the Platform Policy, the court concluded that "because Plaintiff uploaded the Photograph to Instagram and designated it as 'public,' she agreed to allow Mashable, as Instagram’s sublicensee, to embed the Photograph in its website."

The court swatted away a bunch of policy and other arguments that Sinclair made to attempt to convince the court to reach a different result:

- It was irrelevant, the court said, that Sinclair had refused to grant a direct license to Mashable: "Mashable was within its rights to seek a sublicense from Instagram when Mashable failed to obtain a license directly from Plaintiff."

- Nor did it matter that Mashable was not an intended third party beneficiaries under the TOU. As a sublicensee of Instagram, Mashable was an authorized user. Moreover, according to the court, "[w]hether Mashable is an intended beneficiary would only matter if Mashable were attempting to enforce one of the agreements between Instagram and Plaintiff, which Mashable is not."

- The court also declined Sinclair's invitation to invalidate the sublicense based on the complexity of the “circular,” “incomprehensible,” and “contradictory” Instagram terms and policies. In the court's view, "while Instagram could certainly make its user agreements more concise and accessible, the law does not require it to do so."

- Finally, the court rejected the plaintiff's policy argument that it should not enforce the terms of the sublicense because it was "unfair" for Instagram to "force" a photographer to choose to make her account private to avoid granting permission to Instagram to sublicense her photos to third parties via the API. Nevertheless, Judge Wood acknowledged the difficult position that Instagram's TOS poses for a professional photographer:

Unquestionably, Instagram’s dominance of photograph- and video-sharing social media, coupled with the expansive transfer of rights that Instagram demands from its users, means that Plaintiff’s dilemma is a real one. But by posting the Photograph to her public Instagram account, Plaintiff made her choice. This Court cannot release her from the agreement she made.

In other words (and echoing your parents likely said to you countless times), when you play in Instagram's house, you must play by Instagram's rules, and those rules permit syndication, via its API, of content that you designate as "public."

A few observations.

1. The decision sidesteps a thorny copyright issue. Perfect 10, Inc.v. Amazon.Com, Inc., 487 F.3d 701 (9th Cir. 2007), to hold that there is no infringement of the display right when a website publisher links to an image hosted on a third party's server instead of hosting the image on its own server. However, two years ago, Judge Forrest (also sitting in the S.D.N.Y.) startled many in the tech and IP worlds when she rejected the Server Test and ruled that embedding a tweet in a news article violated the copyright owner's display rights. Goldman v. Breitbart News Network, 302 F. Supp. 3d 585 (S.D.N.Y. 2018). The Goldman case settled before the court reached the question of whether the allegedly infringing use had been licensed under Twitter's terms of service.

By ruling that Mashable's use of Sinclair's photo was licensed, Judge Wood avoided weighing in on the question of whether the act of embedding a photograph on a website, as a matter of law, infringes upon the copyright owner's display rights. That question is a complicated one and remains unsettled. Some courts that have considered the issue have followed the so-called "Server Test," embraced by the Ninth Circuit in

In the wake of Judge Wood's decision, the defendants in Bell v. Chicago Cubs Baseball Club, LLC - see this prior post - may want to make a new motion to dismiss based on Twitter's TOS and cite Judge Wood's decision in support.

2. The reasoning of this decision does not support the argument that all embeds are permissible. Sinclair's personal website instead of from her Instagram account, there would be no argument that Sinclair had authorized the use in question. The "all rights reserved" legal notice on the homepage of Sinclair's website should serve as a warning to future embedders: deep link or embed images from Sinclair's website at your own risk!

Judge Woods decision is predicated on the fact that Sinclair, whether she realized it or not, had expressly authorized Instagram to permit Mashable to embed her photo on Mashable's website via Instagram's API. If Mashable had, instead, embedded (or deep linked to) a photograph from

3. Embedding photos through Instagram's API could implicate third party rights.

For example, if a car company were to use Instagram's API to embed one of Sinclair's photographs in a banner ad promoting a sports utility vehicle, a woman recognizably featured in the photograph could plausibly assert a claim that the use of her image violated her right of publicity. If the same woman was wearing a Mickey Mouse tee shirt, Disney might assert a claim of copyright or trademark infringement. (Let's leave aside for now the strength of those claims and possible defenses.) Instagram makes no warranty to publishers and developers who leverage content via Instagram's API; on the contrary, pursuant to the Platform Policy, the publishers/developers are required to indemnify Instagram for claims arising from their use of its API. (Instagram's house; Instagram's rules.) And finally, since this example concerns use in an advertisement, it is important to note that Instagram's Platform Policy expressly require anyone that is leveraging user content via Instagram's API to "[o]btain a person's consent before including their User Content in any ad." A lot to think about.

2020 WL 1847841 (S.D.N.Y. Apr. 13, 2020)

/Passle/5cb04e9a989b6e13ecfcf95d/SearchServiceImages/2025-09-19-19-42-38-376-68cdb22e5c59345ac460df18.jpg)