With the rise of the “gig economy,” millions of Americans have turned to online platforms and mobile applications to navigate the evolving employment landscape and find part-time work. But what exactly do we call these part-time workers—so-called freelancers, side-hustlers, gig-workers—and who gets to do the naming?

A pair of dueling tech companies recently litigated this question in a dispute that made it all the way to the Ninth Circuit. Freelancer and Upwork both offer software platforms that match freelance workers with freelancing jobs. Since 2013, however, Freelancer has held a federally registered trademark for the word “FREELANCER” for goods and services under Classes 9, 35, 36, and 45. The mark, which received incontestable status in 2018, consists of standard characters without claim to any particular font, style, size, or color.

In late August 2020, Freelancer sued Upwork in the Northern District of California alleging trademark infringement and seeking an injunction to restrain Upwork from using “freelancer” with its software, including as a way of distinguishing Upwork’s client‑facing and freelancer-facing mobile application interfaces.

Upwork argued that its use of the word “freelancer” is protected under the fair use doctrine because it only uses it descriptively and in good faith according to the word’s plain meaning. To this end, Upwork submitted evidence that it uses the word “freelancers” to describe its users, and that “freelancer” is a well-known term defined as “someone who is not permanently employed by a particular company, but sells their services to more than one company.”

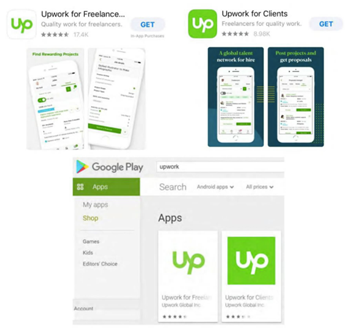

In retort, Freelancer argued that Upwork uses the term “freelancer” as a mark, rather than descriptively, because Upwork uses “freelancer” to distinguish the display names of its applications (“Upwork for Freelancers” versus “Upwork for Clients”), in the notification prompt Upwork sends to its users (“‘Freelancer’ Would Like to Send You Notifications”), and because Upwork displays the term in bold font and capitalized (“Freelancer”) in certain instances.

The district court disagreed with Freelancer’s argument, however, finding that Upwork uses the term in good faith descriptively rather than as a mark. In reaching its decision, the court took note of the fact that Upwork does not list the word “freelancer” among its publicly listed trademarks or use a stylized font or “TM” symbol when using the term. In addition, the district court found that Upwork’s mere use of bold font and capital lettering was insufficient to transform its use of “freelancer” from a descriptive use into use as a mark. On appeal, the Ninth Circuit affirmed, upholding the district court’s finding that Upwork uses the term “freelancer” in good faith to describe its users and that its use is therefore protected fair use under 15 U.S.C. §1115(b)(4).

The Freelancer decision is good example of why businesses should be careful when using a trademarked term to describe their goods or services, particularly when the mark is held by a direct competitor. While not every use of a trademarked term will necessarily constitute fair use, under the logic of Freelancer, a business might lessen its liability by ensuring that its use of any descriptive term is done in good faith according to the ordinary meaning of the term, that the term accurately describes the goods or services to which it applies, that it is accompanied by the business's house mark or branding, and that the term does not appear in an overly stylized manner.

***

Freelancer Int'l Pty Ltd. v. Upwork Glob., Inc., No. 20-CV-06132-SI, 2020 WL 6271030, (N.D. Cal. Oct. 23, 2020), aff'd, 851 F. App'x 40 (9th Cir. 2021)

/Passle/5cb04e9a989b6e13ecfcf95d/MediaLibrary/Images/2026-01-25-21-07-45-516-69768621511eaff31e8fbcf1.png)

/Passle/5cb04e9a989b6e13ecfcf95d/SearchServiceImages/2026-01-24-15-45-55-342-6974e9338a71e5f81a34b101.jpg)