Plaintiff Michael Hayden is an American who, in the late 1980s, was living la dolce vita in Italy, working as an artist and set designer. Among his gigs was designing sets and props for films featuring Italian adult film star (and future member of the Italian Parliament) Ilona Staller, better known as “Cicciolina.” Knowing that Staller was (as he puts it) "fond of snakes," Hayden created and then sold to Staller's company (as he describes it) "a large sculptural work depicting a giant serpent wrapped around a rock pedestal." Hayden alleges in his complaint that the "intended purpose of [his sculpture] was to serve as a work of fine art on which Cicciolina could perform sexually explicit scenes, both live and on camera." Not the sort of product description you see on artsy.net or dwr.com. (You can see Hayden's sculpture here.)

Defendant Jeff Koons is a world-famous artist who has been on the receiving end of several copyright lawsuits over the years (including those covered in this post and this one). In 1989, Koons and Staller appeared together in a series of photographs that were shot in Staller's studio in Rome. In some of the photos, the couple appears to be in the throes of intimate congregation atop Hayden's sculpture. Koons used those photos to create a billboard, canvas and sculpture that ultimately were included in Koons's series titled Made in Heaven. The three works at issue (with links) are:

- Made in Heaven (1989) (lithograph billboard)

- Jeff and Ilona (Made in Heaven) (1990) (a polychromed wood sculpture)

- Jeff in the Position of Adam (1990) (oil inks on canvas)

Hayden claims he was unaware of Koons's series until 2019, when he read an article about a lawsuit filed by Staller against Sotheby’s that included a photograph of one of the challenged works. After obtaining a copyright registration for his sculpture, under the title Il Serpente for Cicciolina. Hayden sued Koons in the Southern District of New York, alleging, among other things, copyright infringement and violation of the right of attribution under the Visual Artists Right Act ("VARA"). Hayden seeks damages and various flavors of injunctive relief.

Earlier this month, Koons moved to dismiss the complaint. In his brief, Koons makes two principal arguments.

Is a Snake Sculpture, Designed as a Platform for Adult Film Antics, a Useful Object?

First, Koons argues that the sculpture should be categorized as a useful object that has no claim to protection under copyright law. In his brief, Koons never refers to Hayden's work as a sculpture; instead it is a "prop" or a "platform."

The Copyright Act defines a “useful article” as “an article having an intrinsic utilitarian function that is not merely to portray the appearance of the article or to convey information.” (17 U.S.C. § 101.) Copyright protection does not extend to the mechanical or utilitarian aspects of a useful article; however, pictorial, graphic, or sculptural features that are incorporated in a useful article maybe subject to copyright protection "if, and only to the extent that, such ... pictorial, graphic, or sculptural features can be identified separately from, and are capable of existing independently of, the utilitarian aspects of the article.” (17 U.S.C. § 101 (definition of "pictorial, graphic or sculptural work")). See Star Athletica, L.L.C. v. Varsity Brands, Inc., 578 U.S. 959 (2017).

In his brief, Koons contends that Hayden cannot deny that his sculpture is a useful article since, in the complaint, he alleges that it was designed specifically to be a stage on which Staller would perform. Moreover, Koons argues, any potentially protectable sculptural features incorporated in Hayden’s sculpture (such as the serpent design) are not separable, or capable of existing independently, from the rest of the work. On the contrary, Koons claims, "the serpent and the rock are inextricably intertwined and barely distinguishable from one another and, together, they comprise the entire utilitarian platform."

Was Koons's Use of the Sculpture a Transformative Fair Use?

In the alternative, Koons argues that even if Hayden's sculpture qualifies for copyright protection, the complaint should be dismissed because Koons made a transformative fair use of the sculpture in his Made in Heaven series.

Koons's analysis of the first statutory fair use factor (purpose and character of the use) begins with the Second Circuit's recent opinion in Andy Warhol Found. for Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, 11 F.4th 26, 37 (2d Cir. 2021) (which we covered extensively in this post, this post and this one). In Warhol, the court sifted through a "greatest hits" of Second Circuit fair use cases to provide guidance in cases (like this one) where both the primary and secondary works are visual works that, at least to some degree, share the same "purpose": i.e., to serve as art. Two of those cases involved works by Koons.

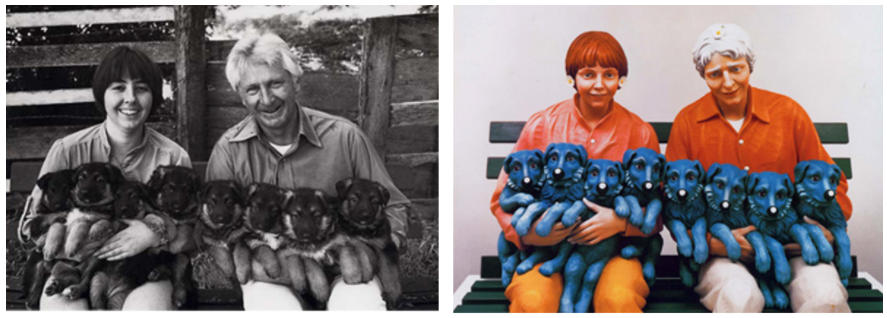

In the first, Rogers v Koons, 960 F.2d 301 (2d Cir. 1992), the court held that Koons's use of the photo on the left to create the sculpture on the right was not transformative:

By contrast, in Blanch v. Coons, 467 F.3d 244 (2d Cir. 2006), the court found that Koons's use of the advertisement on the left was transformative when incorporated in the work on the right:

Koons argues (naturally) that his use of the Hayden's snake sculpture in Made in Heaven is on all fours with Blanch and nothing like Rogers:

"Based on a side-by-side visual comparison of the Made in Heaven artworks with Hayden’s platform, the transformative purpose and character of Koons’s artworks in this case are just as apparent as they were in Blanch: Hayden’s platform is not the major or dominant component of the expression created by Koons’s artworks (indeed, in Made in Heaven and Jeff in the Position of Adam, Hayden’s prop is not even recognizable); unlike the original photograph in Rogers, Hayden’s platform is not the only element of Koons’s artworks, which do not recognizably derive from, or reflect the essential elements of, Hayden’s platform; as with the original photo in Blanch, the features of Hayden’s platform have been radically altered in Jeff and Ilona (Made in Heaven) so that the serpent has been transformed from a mere component of a somber, static, monochromatic mass into a vibrant and dynamic creature with iridescent green and orange hues and a bright red flicking tongue, surrounded by flowers and waves of water; unlike Rogers but like Blanch, Hayden’s prop is juxtaposed with other images, notably Koons and Staller in the roles of Adam and Eve (as can be deduced from the titles of the artworks and the way in which Staller emerges from Koons’s rib in Jeff in the Position of Adam); and, as in Blanch but not Rogers, Hayden’s serpent serves as raw material in a new work, becoming the serpent in the Garden of Eden instead of a mere part of a utilitarian stage prop." (Citations omitted.)

Moreover, Koons argues, the use of Hayden's sculpture-cum-platform was transformative in other senses, including:

"By depicting Staller on her authentic sets and in her normal working environment, including atop Hayden’s platform, the Made in Heaven series also blurred the line between art and pornography and, because the famous porn star had become the artist’s lover, the line between art, life, and the media while also testing the boundaries between art and mass culture and the relationship of artists to celebrity. This too was transformative." (Citations omitted).

Koons makes the arguments you would expect to support his position that the other statutory factors also tilt in his direction. The second factor (nature of the copyrighted work) favors fair use, Koons claims, "because Hayden’s platform is utilitarian and has been published." Likewise, according to Koons, the third factor (amount and substantiality of portion used) supports a finding of fair use because "the quantity and quality of the materials copied was reasonable in relation to a valid transformative purpose." And under the fourth factor (effect on market), Koons argues that Hayden has failed to identify any cognizable market harm, and that the broader public interest is served by allowing the use.

Anticipating that Koons would mount a fair use defense, Hayden included in his complaint a preview of the arguments we can expect in his opposition papers. Here is a flavor:

"The use, character, and meaning of the Hayden Work within the Infringing Works does not deviate in any way from the intended original use, character, or meaning of the Hayden Work. Indeed, whereas the intended purpose of the Hayden Work was, inter alia, to serve as a platform, backdrop, and context for Cicciolina’s sexually explicit performances, Mr. Koons has admitted repeatedly that his purpose and intention for the Infringing Works was simply to insert himself into Cicciolina’s sexually explicit performances and thereby increase his own notoriety. The Infringing Works do not place the Hayden Work in a new context, nor did they add any new expression, meaning, or message to the Hayden Work. No reasonable observer would conclude in a side-by-side comparison that the Infringing Works created new information, aesthetics, insights, or understandings with respect to the Hayden Work."

Surely, more will follow when Hayden responds to Koons's motion.

What About An Implied License?

The motion to dismiss does not address a potential implied license defense: specifically, that because Hayden sold the sculpture to Staller for the express purpose of using it as a platform on which she would be photographed, he had granted to Staller (and, by extension, to Koons) an implied license to photograph the sculpture. (See this post and this post on recent cases where implied copyright licenses have been recognized by courts.) In his complaint, Hayden anticipates this argument and alleges that he "never granted Mr. Koons permission to use the Hayden Work in the Infringing Works, nor did any license Mr. Hayden may have implicitly granted to Cicciolina [or her studio or manager] permit Mr. Koons to use, copy, make, or profit from copies of the Hayden Work." Hayden also drops a footnote that hints that there could be a complicated choice of law lurking here: "to the extent that Italian Law applies to this transaction, it is possible that no rights to use, display, copy, or exploit the Hayden Work could have been transferred, explicitly or implicitly, to anyone absent a written instrument providing for such transfer, regardless of intent." If the case is not dismissed and proceeds to discovery, we can expect that the implied license theory will get some play.

Hayden vs. Koons,

No 21-cv-10249 (LGS) (S.D.N.Y.)

/Passle/5cb04e9a989b6e13ecfcf95d/SearchServiceImages/2025-10-27-14-22-00-425-68ff8008186d67c4aefaf148.jpg)

/Passle/5cb04e9a989b6e13ecfcf95d/SearchServiceImages/2025-10-24-19-43-40-434-68fbd6ec291080c26720ada2.jpg)

/Passle/5cb04e9a989b6e13ecfcf95d/SearchServiceImages/2025-10-22-18-33-24-281-68f9237430555bb786bfaa03.jpg)