Harry Winston was known in his day as the "King of Diamonds" and the "Jeweler to the Stars." The company he founded in the 1920s became world famous not only for its innovative jewelry designs, but also for draping a long list of celebrities in pricey ice. Winston's street cred was such that Marilyn Monroe name checked him during her iconic performance of "Diamonds are a Girl's Best Friend" in the film Gentlemen Prefer Blondes: "Talk to me, Harry Winston, tell me all about it!" (That's respect.) A Harry Winston piece is a prized possession, out of reach for most of us, with a price point to be found, as Shiela E would put it, in the section marked “if you have to ask, you can’t afford it lingerie."

The company that survived the man, Harry Winston SA (now owned by the Swatch Group), tried to register copyrights in these eight jewelry designs:

In 2019, the Copyright Office refused registration, finding that the pieces did not “contain any design element that is both sufficiently original and creative.” When Harry Winston sought reconsideration, the Copyright Office doubled down on its refusal, ruling in 2020 that the jewelry designs did "not contain the requisite creativity necessary to obtain copyright registration" because they consisted of "a garden-variety combination" and "simple arrangement" of unprotectable geometric elements and colors.

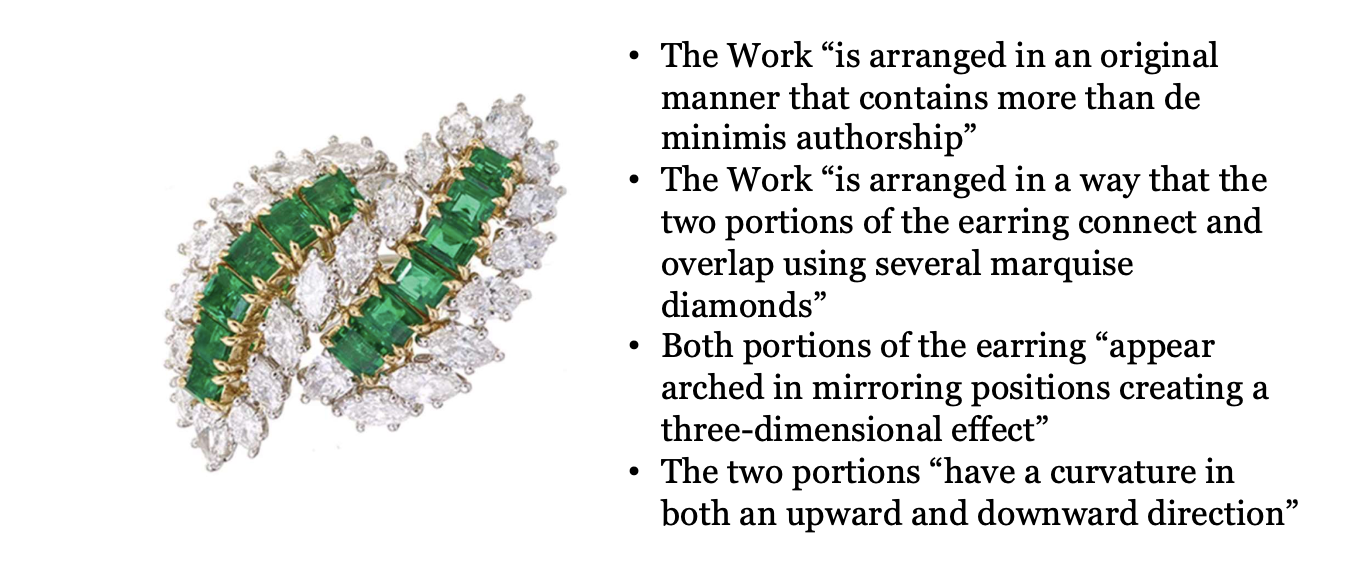

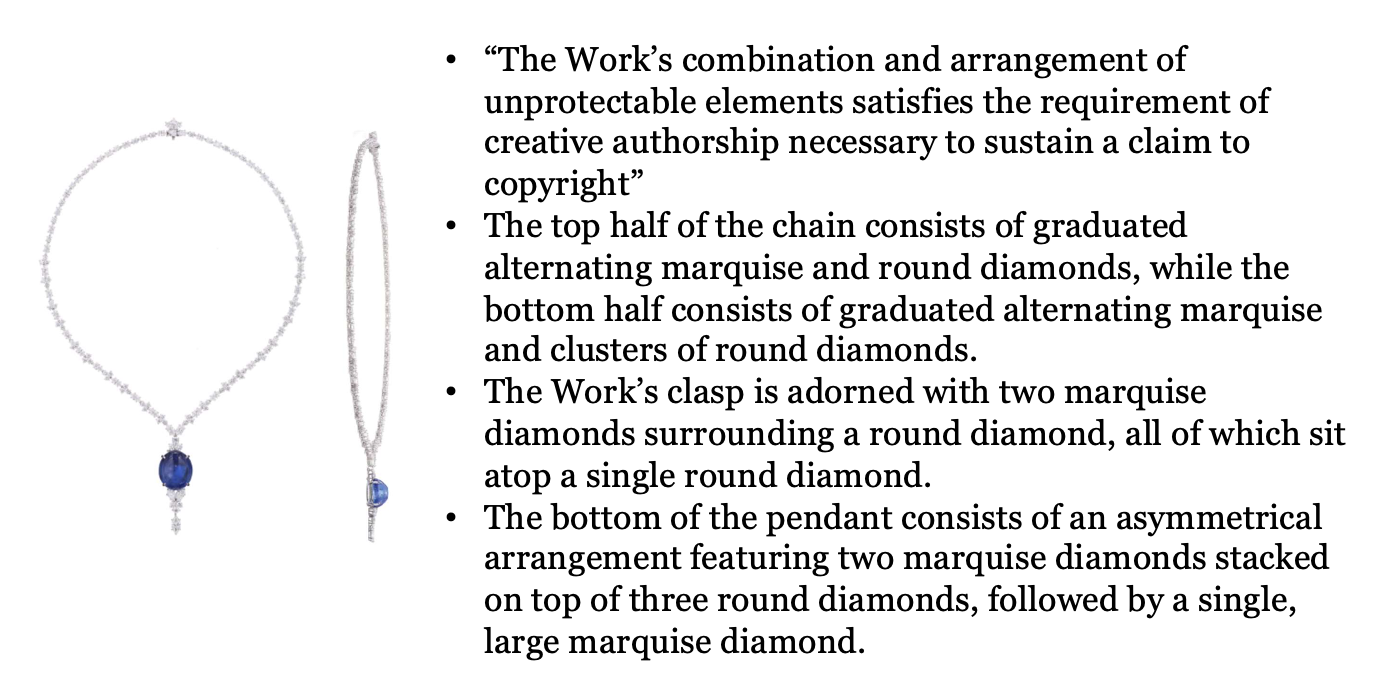

Feeling the sting of the Copyright Office's ding of its request to register its bling, Harry Winston sought reconsideration before the Copyright Review Board (see 37 C.F.R. § 202.5(c)). This time, the company fared better: the Review Board concluded that three of the eight works contained the requisite creativity necessary to sustain claims to copyright.

Before you read further, can you guess which three?

Jewelry designs are potentially copyrightable as sculptural works, the definition of which includes “works of artistic craftsmanship." (17 U.S.C. § 101.) Of course, only "original" design elements are protectable - i.e., those that were created independently (and not copied from pre-existing works) and that possess a modicum of creativity. In addition, protection is not afforded to the mechanical or utilitarian aspects of jewelry (like the functional aspects of a clasp or the cut of a gemstone intended to maximize light refraction). And common or standard design elements are not protectable: things like basic geometric shapes, arrangements, and patterns. Those are building blocks available to all designers.

However, copyright protection can extend to an original "selection and arrangement" of common elements, where the elements are numerous enough, and their selection and arrangement original enough, such that their combination constitutes an original work of authorship. This is true across all creative genres. The composer of a song can take familiar, stock musical elements and arrange them in a way that is sufficiently creative (see this post), and a collagist can create a protectable work of art by selecting and arranging, in an original way, public domain elements (e.g., ancient hieroglyphics, public domain photos, shapes, colors, words, etc.) (see this example).

These are the three pieces that the Copyright Review Board determined could be registered based on the selection and arrangement of unprotectable elements:

The Board concluded its analysis with a cautionary note:

"To be clear, the Board’s decisions regarding [these Works] relate only to the Works as a whole - the specific arrangements of various shapes - and do not extend individually to any of the standard or common elements depicted in the Works, such as rectangles, circles, cones, ovals, spheres, and elongated ellipses or the faceting of the individual stones."

For the other five designs, the Copyright Board upheld the registration refusals, finding that the designs consisted only of commonplace design elements that were arranged in a "common or obvious manner.” But, of course, that doesn’t mean they aren't pretty.

The Copyright Review Board's decision can be found here.

/Passle/5cb04e9a989b6e13ecfcf95d/SearchServiceImages/2025-10-27-14-22-00-425-68ff8008186d67c4aefaf148.jpg)

/Passle/5cb04e9a989b6e13ecfcf95d/SearchServiceImages/2025-10-24-19-43-40-434-68fbd6ec291080c26720ada2.jpg)

/Passle/5cb04e9a989b6e13ecfcf95d/SearchServiceImages/2025-10-22-18-33-24-281-68f9237430555bb786bfaa03.jpg)