The late Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, a/k/a the “Notorious RBG,” died in September 2020. But, what can only be described as the art world’s obsession with using RBG as its muse, lives on. As does legal controversy that surrounds that art and its reproduction. Just this week, an Atlanta federal judge tossed a photography agency’s copyright infringement action against Georgia artist Julie Torres for her use of a photograph of late Justice Ginsburg, holding the agency does not have standing to sue.

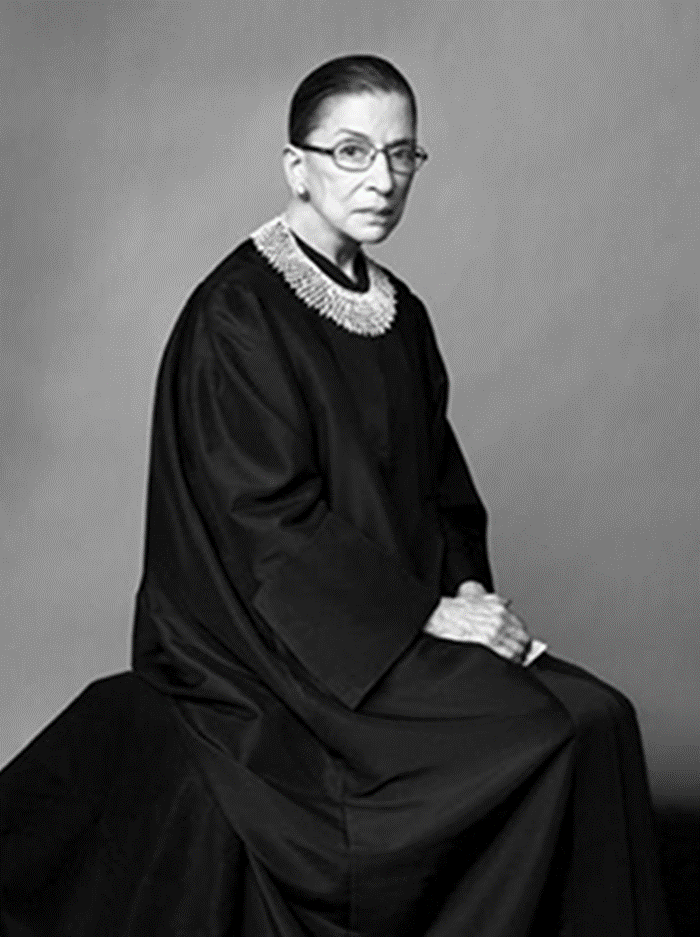

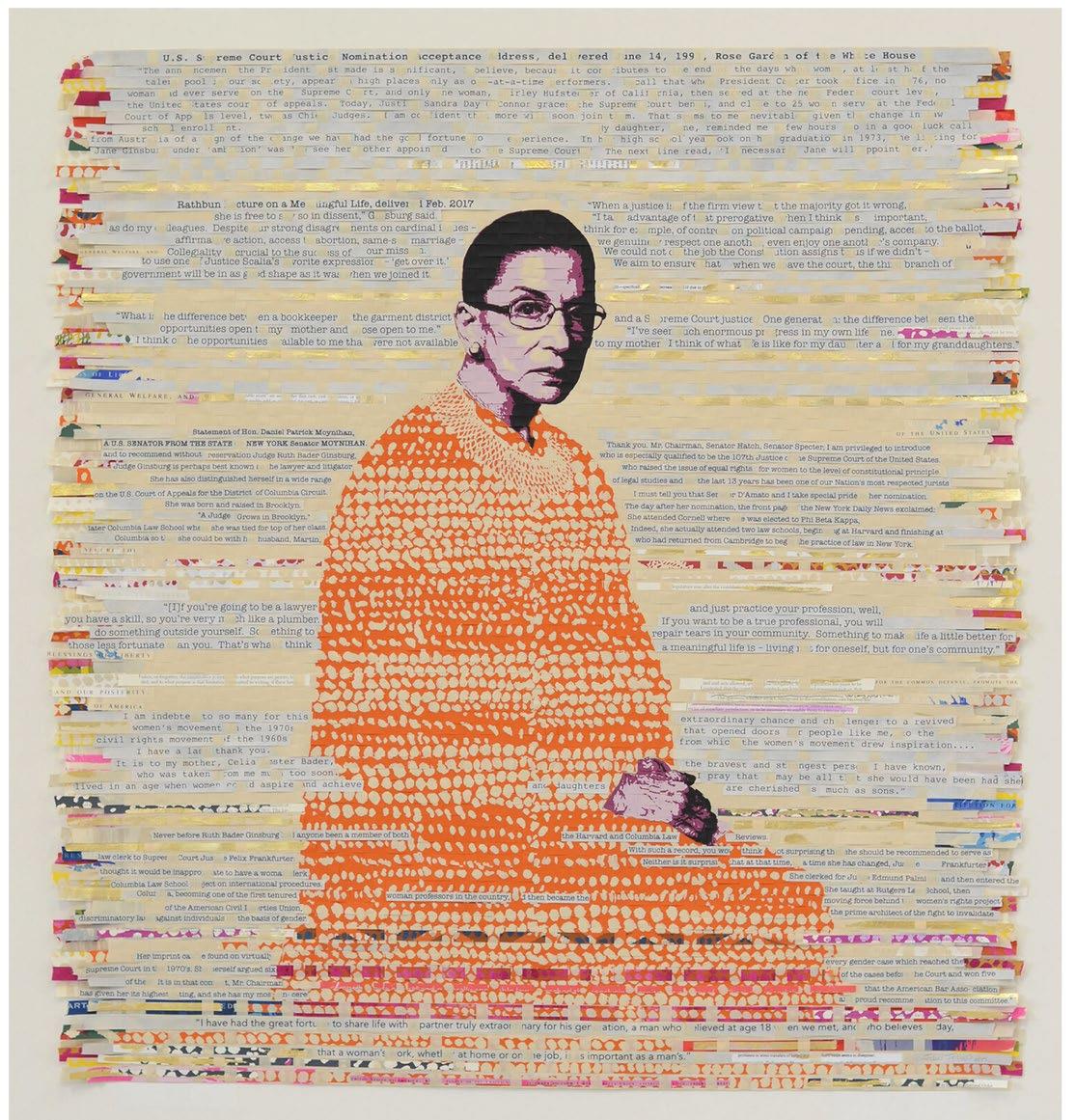

Creative Photographers Inc. sued Torres in November 2021 for her alleged unlicensed use of Ruvén Afanador’s 2009 photo of late U.S. Supreme Court Justice. Creative says Torres produced screen prints, mixed media works, and limited addition prints of a copyrighted photograph of Justice Ginsburg taken by Alfanador in 2009. Torres allegedly sold her works (for up to $12,000 per work) without first obtaining a license to use Afanador's protected photograph.

Ruvén Afanador’s 2009 photograph titled "Ruth Bader Ginsburg":

An example of Julie Torres's works, titled "All I Ask":

(Court Documents).

According to Creative, Torres explicitly omitted Afanador's name and copyright information, and refused to acknowledge or credit the photographer. Torres also improperly authorized the public display of her art featuring Afanador's photo at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City and other art galleries. The galleries were not named as parties in the lawsuit.

Torres moved to dismiss the agency’s copyright infringement claim, arguing the commercial photography agency – which doesn’t actually hold copyrights in the photo – lacks standing. Indeed, the Copyright Act contains a statutory standing requirement: to have statutory standing to bring an action for copyright infringement, a plaintiff must be the legal or beneficial owner of an exclusive right in a protected work. “Exclusive rights” are defined in Section 106 of the Copyright Act and include (in relevant part) the right to reproduce the copyrighted work, prepare derivative works based upon the copyrighted work, and distribute copies of the copyrighted work.

Creative argued that its agreement with Ruvén Afanador granted the agency the exclusive rights not just to sell his photographs, but to license them too. But Judge Boulee found that the plain language of Creative’s agreement with Afanador simply makes the agency Afanador's exclusive agent, and not his exclusive licensee. Even if the agreement did convey to Creative an exclusive license – which it does not – the agreement does not contain language suggesting that it confers to the agency “the exclusive right to authorize the preparation of derivative works based upon the copyrighted work.” And a plaintiff cannot sue for infringement of the right to prepare derivative works unless that plaintiff actually holds that particular right. In other words, the conveyance of one exclusive right (e.g., the right to distribute) does not confer standing to enforce a different exclusive right (e.g., the right to prepare derivative works).

The court declined to address Torres’ fair use argument, noting that fair use requires a fact-intensive analysis and, for that reason, it is improper to analyze the affirmative defense of fair use on a motion to dismiss. Creative Photographers has 14 days to file an amended complaint.

/Passle/5cb04e9a989b6e13ecfcf95d/MediaLibrary/Images/2026-01-25-21-07-45-516-69768621511eaff31e8fbcf1.png)

/Passle/5cb04e9a989b6e13ecfcf95d/SearchServiceImages/2026-01-24-15-45-55-342-6974e9338a71e5f81a34b101.jpg)