What happens when someone buys a work from a famous artist, cuts it up and then sells the constituent parts (as well as what remains of the original)? Is that a violation of the Visual Artists Rights Act ("VARA"), which is intended to prevent the destruction or mutilation of works of recognized stature? Or is it a transformative use of an existing work and therefore protected under the "fair use" doctrine.

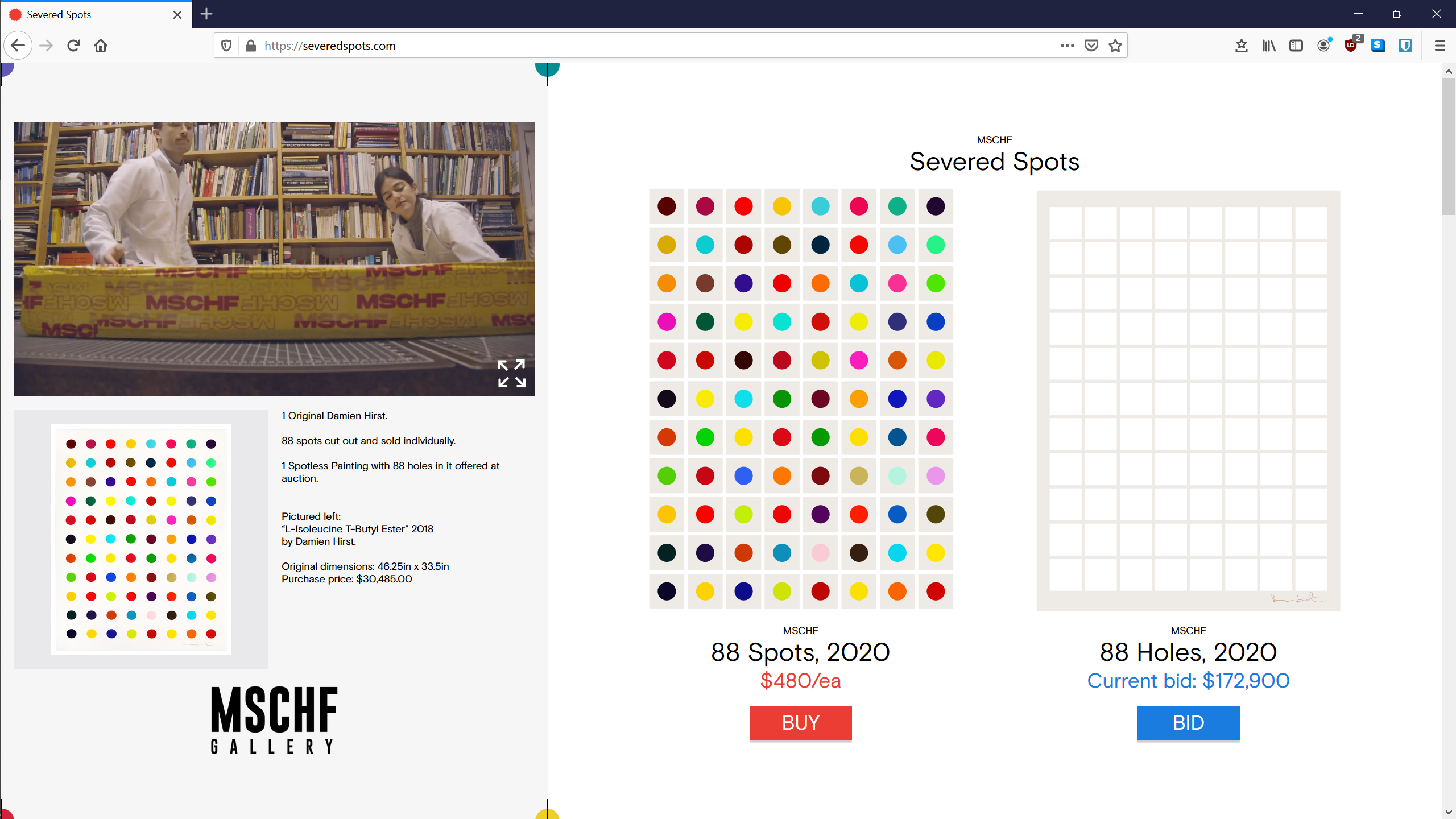

A Brooklyn collective, MSCHF, purchased a Damien Hirst spot work for just over $30,000, dissected it into 88 spots, and sold each spot for $480 (totaling more than the value of the original), and is auctioning off the original work with holes, with current bidding in the six figures. While we have not heard any report that Hirst, himself long known for creating controversial work, objects to MSCHF’s conduct, MSCHF’s activity raises interesting questions around when one can lawfully destroy another’s artwork in order to make a new work.

The Hirst Work and the MSCHF Work

Damien Hirst, who came to prominence in the 1990s as of of the “YBAs” (Young British Artists), commonly uses found objects and produces shocking imagery (such as sharks in formaldehyde and diamond-encrusted skulls). Hirst reportedly is one of the wealthiest artists alive, and is well known for his iconic spot paintings. MSCHF claims to have purchased one of these spot works, “L-Isoleucine T-Butyl Ester” (2018) (produced as a limited edition) for $30,485. The Hirst work features eight columns and eleven rows of colored spots (88 spots).

On its website, MSCHF features a video of its efforts to re-brand the Hirst work as a new project entitled “Severed Spots.” In the video, MSCHF members carefully unpack the Hirst work and painstakingly cut out the spots with an X-Acto knife, signing each of them. On its website, MSCHF offered for sale each of the “88 Spots” at $480 (which are sold out), and are auctioning off the now dissected husk of the Hirst work as “88 Holes” and the bidding has purportedly already exceeded $170,000.

What prompted MSCHF to do this? MSCHF’s prior projects include infusing Nike shoes with holy water and selling them as “Jesus Shoes” and a dog collar that curses every time your dog barks. MSCHF claims in its “manifesto” that it created “Severed Spots” as a commentary on the state of the art market and the purported commodification of art through the increasing practice of fractionalized ownership (whereby a pool of investors own undivided interests in a work of art). MSCHF’s manifesto is also critical of Hirst’s works, suggesting they are among those “clone-stamped wall works” by the art world’s “whales (one wonders whether our boy D perhaps even literally leapt over that shark, as it sank in it’s [sic] formaldehyde sea).”

The Rights of Artists

This project, along with the case of the musician shooting then selling another’s painting, which we blogged about here, raises novel questions about when an artist can lawfully destroy another’s work without running afoul of the rights held by the underlying artist.

Creating works through destruction has been recognized for decades as a valid manner of cultural production. Perhaps the most notable example is Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953) by Robert Rauschenberg. Done before VARA’s enactment, and with the consent of Willem de Kooning, Rauschenberg erased a de Kooning drawing, and added his own name on an inscription in a gilded frame. Other well-known episodes of artists using, destroying, or lampooning art in an attempt to make a different work, intended to be impactful for different reasons, include the spontaneous shredding of a Banksy picture at auction, a performance artist eating the banana from Maurizio Cattelan’s “Comedian” work (a banana duct taped to a wall), and performance artists jumping on My Bed by Tracey Emin.

Under VARA, codified at 17 U.S.C. § 106A, visual artists enjoy a limited right of integrity for “works of visual art,” as that term in defined in the statute (more on that later). Under VARA, an artist has the right to:

“(A) to prevent any intentional distortion, mutilation, or other modification of that work which would be prejudicial to his or her honor or reputation, and any intentional distortion, mutilation, or modification of that work is a violation of that right, and

(B) to prevent any destruction of a work of recognized stature, and any intentional or grossly negligent destruction of that work is a violation of that right.”

Though what will qualify as a work of “recognized stature” is determined on a case-by-case basis, the Second Circuit ruled in the 5Pointz case (discussed here) that there is a relatively low bar to achieving this stature, and iconic works by famous artists surely would meet this standard. A “work of visual art,” in turn, is narrowly defined in 17 U.S.C. § 101 to only include a subset of the media in which contemporary artists now work, including only paintings, drawings, prints or sculptures (but only in limited editions of 200 or fewer copies), and exhibition-only limited runs of photographic prints. As an additional limitation, the artwork must also be copyrightable in order to enjoy protection under VARA.

Notably, though, when Congress enacted VARA into law 30 years ago, it made these moral rights subject to the fair use affirmative defense set forth in 17 U.S.C. § 107. While fair use may well have only narrow application to artists’ rights under VARA, and it may be difficult for some to imagine how the mutilation of a well-known work could ever be considered a fair use, there is a dearth of case law applying fair use to VARA. Given that the creation of art can involve the destruction of other art, the development of this aspect of VARA may inform artists of their rights and obligations when using artwork created by other living artists.

/Passle/5cb04e9a989b6e13ecfcf95d/MediaLibrary/Images/2026-01-25-21-07-45-516-69768621511eaff31e8fbcf1.png)